Sustainability is obviously more than numbers and measurements. We know this but sometimes decision making loses sight of our motivations. Consequently, art has a big role to play.

The synergy between art and sustainability is strong. The picture above is from my 2005 Graham F Smith Peace Trust dinner talk – below. And this year the integration was partly the subject of a joint USA Harvard, Australia and China Climate Change and Society colloquium here.

Read on for more – how art and sustainability are creating more than the sum of their parts.

Sanctuaries

Good evening, welcome and thank you to the Graham F Smith Peace Trust for giving me the opportunity to talk tonight.

I titled this talk Sanctuary as, with its multiple meanings, it sums up relationships between art, human rights and the environment.

Sanctuary and the arts I’ll touch on are multifaceted.

I want to illustrate the ways in which art acts and then the different levels at which it acts

For example, at a personal or practical or political level:

- our personal sanctuaries like home can reinvigorate us.

- Environmentally we have ecological sanctuaries, different species occupy their own niches within the world and at a more local level we create specific sanctuaries for whole environmental systems.

- And sanctuaries can be a refuge from violence.

Art also acts in many different ways:

- It exposes assumptions and accepted norms.

- It confronts unconsciousness.

- It actively combines form and function – acting to repair the physical environment.

Most of all though it inspires holistic change. If you like art is a dot point for progressive change encompassing our society and the interrelated dependencies between peace, the environment, human rights and justice.

And, yes, this is a mouthful. You can see why we need better summaries. Art can do this!

But before we look at this some people may recognise the inspiration for this talk from the logo on the screen. Its from the Glasgow museum of modern art’s recent exhibition on contemporary art and human rights.

Are there any Glaswegian’s here tonight?

🙂 Relief …. better be careful but

Glasgow may seem like a slightly strange place to find inspiration. You may be asking what the city has to do with art’s role in inspiring protest, creating shelter and a more sustainable world – the theme for this talk.

I certainly have some of this reaction as I spent my childhood there and yes it was a tough town.

But I’m also very lucky as my parents still live there and my mother is a voluntary museum guide. She says the people behind the sanctuary exhibit believe that art is a highly important means of communicating with a wide public, and of saying difficult things, sometimes in difficult ways.

We’ll get to say things in different difficult ways next, but first a little bit.

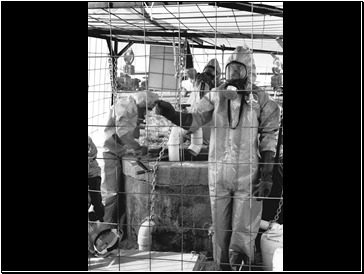

In this picture, Greenpeace is involved in shutting down a very toxic waste pipe. You can see the plumbers admiring their handiwork in the background – the outfall has had a pipe and tap attached to it and the tap’s been turned off.

This is a theme that runs through tonight: exposing practices – in this case, waste dumping to the public eye. And in so doing bringing it into people’s consciousness so change can occur.

Toxic waste however is also widely shipped around the world. The injustice of this has been successfully highlighted primarily by images. In 1994 the power of these images helped changed an international convention. it now bans practices like the one on-screen (American computer scrap sent to China and returned courtesy Greenpeace).

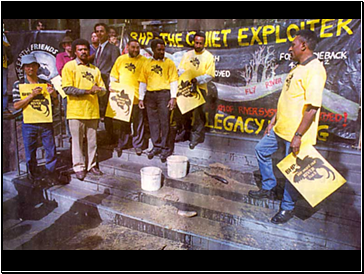

Political environmental protest and using images to highlight injustice is often the only way of making issues public. this one is Ok Tedi. This photo is taken on the steps of BHP’s corporate office in Melbourne, April 2000, and ensured coverage of a relaunched legal action with PNG villagers suing the company.

These protests sometimes meld closely with more traditional art forms. This is an ice sculpture in front of the opera house.

It marks the entry into force a few months ago of the Kyoto protocol, a worldwide start to addressing climate change.

This creates a visual medium for something that is otherwise very abstract; gas emissions into the atmosphere.

But do images actively inspired change, creating environmental sanctuaries, as opposed to highlighting issues?

Emphatically yes and recently about half a million times.

These butterflies are near the proposed protected wilderness area in the west of this state.

500,000 hectares are to be protected from mining with the strongest protection available in South Australia, declared a wilderness area.

The butterflies are part of a series highlighting this win and also that the area misses protecting some highly important and significant places.

Images have catalysed a vast amount of environmental change: From the famous Peter Dombrovskis

picture which brought the wild beauty of a remote part of Tasmania into the consciousness of many. This picture is Rock Island Bend on the Franklin River in Tasmania and was taken in 1979.

On the screen now is an area that may someday be as well known, through Bill Doyle’s photography. He also took the earlier butterfly shot.

This is Coongie lakes in the far NE of this state.

A version of this photo was bought for the Premier of South Australia, Mike Rann, by his Environment Minister John Hill.

The area is now protected from mining and grazing, particularly from oil exploration.

Very few people would know about these places without these pictures. They are remote and inaccessible for the majority of Australians.

Any one been to Googs in Yellabina, Coongie Lakes, or Rock Island Bend?

I’ve managed one of the three, and so you can see how critical these images are for the protection of these environmental sanctuaries.

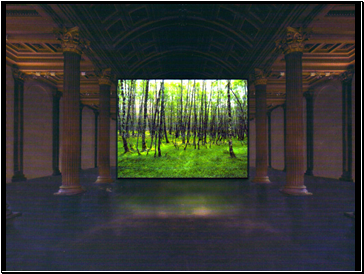

Artists have also been commissioned – in this case Matthew Dalziel and Louise Scullion – to create new work specifically demonstrating the beauty and complexity of the environment as well as drawing inspiration from environmental activism.

The installation above, storm, takes its title from a quote by the Scottish environmentalist John Muir

(he lived from 1838 to 1914. We Scotts have always been ahead of the times).

John described nature as:

‘a storm of energy, eternally flowing from use to use, from beauty to yet higher beauty’.

He argues that the world we inhabit is in a continual state of flow and flux and that everything is dependent on, and affects, everything else. He also promoted the idea that beauty is not merely an aesthetic concern, but a recognition that the complex interactions and diverse systems, that are our world and ecosystems, is a thing of beauty in and of itself.

Dalziel and Scullion say the images they bring to life in the storm are revealing our ecology and a rich interaction of things like weather animals and people over vast expanses of time.

I think they also capture an essential part of our world. It is a four-dimensional place with time as a key component of both environmental impacts and social change.

They do this as to experience the whole of Storm you need to visit the gallery over a 3 week period. This is a bit of a challenge if, like me, you have trouble staying in Glasgow for more than 8 hours. But you now have an acceptable cultural reason for drinking whiskey in Scotland for 3 weeks

But environmental and human rights activism through public art has not just been about beauty and wilderness.

The power of images, melded with performance or experiences highlight what is often mentally remote many. This can be one of the many aims and purposes of art as well as environmental actions.

It is also often one of the few ways that many issues can be made to cut through and by which people can empathise with a particular issue.

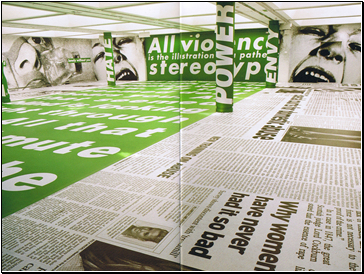

Barbara Kruger, the artist here, uses design, production and display techniques from mass advertising in her art to highlight the words and phrases that characterise us.

Her work on the screen is the centrepiece installation from the rule of thumb; contemporary art and human rights which is a 13 month long art program addressing violence against women.

She says

‘For many years I’ve tried to make work about how we are to one another, about how we treat each other. Categorising a practice and calling it feminist or political (and I would add environmentalist) tends to close down meanings and has a marginalising effect

She tries to address notions of power and how they make us look and feel: how they dictate our futures and our past. How power threaded through culture She says that

‘Power and its politics and hierarchies exist everywhere: in every conversation we have, in every deal we make, in every face we kiss’

And Barbara confronts this power in public art, like on this domestic violence billboard in a train station,

These themes also run through some of the activism I want to show next.

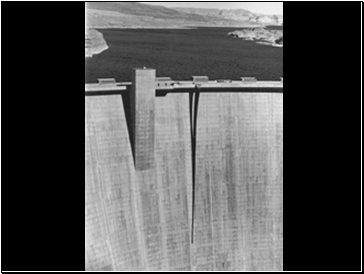

For example, here’s an installation of a huge plastic crack on a dam to make the point that the structure is corrupt. Alternatively, the crack corrupts the structure in a way that is visible.

This a favourite pictures. Before this crack in Glen Canyon dam on the Colorado river in 1981 the corruption was largely invisible. At the time many people were actively writing and publicising the flooding of a unique part of the US caused by the dam. It would mean that an environment that had been shared by everybody would soon be used for the profit of a few (eg irrigators and subsidised power users).

However this is a tragedy of the commons argument and does not necessarily resonate with a mass of people. But it can be brilliantly illustrated.

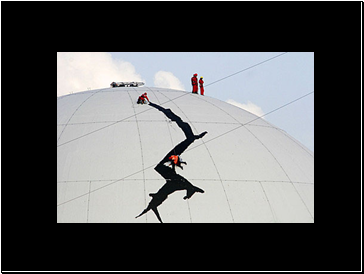

Not surprisingly cracks are a concept that have seen a bit of use in activist art for obvious reasons that is

they can be an ultimate symbol of issues.

Here the canvass is a nuclear power plant in Zeeland, Netherlands.

Greenpeace is painting this crack onto a reactor that is old and many regard as not safe.

The Dutch government agreed to shut it in 2013 but is now considering keeping it open.

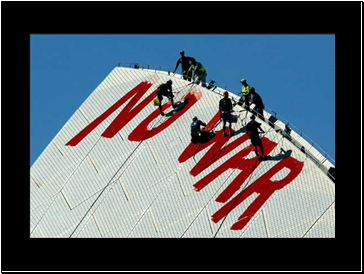

Moving from symbols imposed on structures as statements to statements imposed on symbolic structures.

Here’s one of the ultimate symbols of Australia used as a canvass.

( March 2003 )

As I mentioned before, most importantly it is the remote and out of sight issues that art and visual imagery can bring to people.

Australians environmental footprint is worldwide, for example, we source the copper for our electrical wiring from mines in PNG and Chile, via perhaps Hamburg in Germany to smelt it, and into an appliance, car or house and then back around the world to Australia.

Somewhere in this chain the original source and the impacts are bound to get lost. This is important as without the consumers being conscious of their impacts its very hard to change practices.

Also, let’s face it, it’s unrealistic that an individual should be aware of and take into account the full production chain that leads to the creation of all the various individual parts of, say a fridge. Greenhouse load, wage and labor conditions, pollution at all stages of production, the ultimate fate of waste etc?

So we need something more direct and two examples I wanted to talk about highlight issues in PNG. You saw Ok Tedi earlier. By 2001 this mine which dumps 60,000 tonnes of waste into the Ok Tedi and then Fly River every day was not news. the vision was not new, and while the impacts were apparently less than 12 kms from the Australian border, just above the Torres Strait Islands, few had the issue in the front of their minds in Australia. This mine was once the biggest copper mine in the world (there are 3 large ones now).

Similarly, illegal logging roads are pushing through the PNG western province forest, cutting timber for consumption in far richer countries.

So vision Is critically important. It can publicise what is at stake.

It can also catalyse change and, if tightly focused, help shift a whole complex system.

I am saying that peace, environmental change, justice, equity and civil society are very closely linked.. It’s a relationship that art highlights at many levels, which is what I want to talk about next, personal, practical and political art demonstrating these interdependencies.

Others though also make the point about the interrelationships of issues, particular Professor Mjos who is the Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee.

In awarding the peace prize in Oslo on December 2004 to African environmental activist Wangari Maathai here’s what he had to say on this very subject:

This year, the Norwegian Nobel Committee has evidently broadened its definition of peace still further. Environmental protection has become yet another path to peace

The program Wangari runs, and a central focus of her winning the peace prize makes connections between personal actions and the problems in the environment and in society. She says:

Her wining of the prize has also enhanced the literary discipline of Eco-criticism, a relatively new approach to literature which particularly in Africa highlighting the inter-relationship between art and the natural world.

Think back to the picture painted by Joseph Conrad’s book Heart of Darkness, the Western view of Africa as a baffling space which, has to be tamed and controlled. Its one that needs challenged on many levels.

Wangari does this in part through working with her people’s culture and its arts for individual awareness as well as political change.

So first what about art acting at an individual personal level?

This is my own personal space. David Reid is an Adelaide artist and the painting is of spring in the gully and my birthday present. I also live in Waterfall Gully and the picture comes to life in the gully’s light.

For me it works in part by emotionally connecting me to my environment, the beauty of it, complexity, change, and the values in it.

At a practical level art can also be environmentally functional this living sculptures is cleaning and filtering water.

Its made of mosses, ferns and other plants growing on stone and concrete.

It provides ecological and aesthetic solutions to water quality and water quantity problems.

Jackie Brookner says that her art:

And at the political level this is one of those images that grabs your attention straight off. It hooks me in to know more. You find out its actually in the German parliament building, the Reichstag in Berlin. It was designed when parliament moved back to Berlin in 1998 by Hans Haacke.

He proposed that the words Der bevolkerung – to the population – be spelled out in 4-foot high neon letters in the centre of one of the Reichstag’s courtyards.

This was not an uncontentious proposal. It goes straight to German history, since 1916 Dem Deutschen Volke -to the German people – has been inscribed in the same lettering above the Reichstag’s entrance.

Hans says to the German people it

‘can be read as referring to an ethnically defined people rather than to a people as understood in the tradition of the French revolution. Bertolt Brecht suggested a change that would go to the heart of this – replacing the word ‘volk’ by the word bevolkerung (population) which includes everyone.

This art is also the story of a personal struggle as despite the committee in charge of the art for the Reichstag approving Hans’s proposal by 9 to 1, the sole opponent waged says Hans:

‘a determined campaign to prevent its realization’

It took two years for the proposal to eventually approved by a 260 to 258 vote in parliament.

Members of the parliament are invited to bring soil from their election districts to spread around the neon letters of the dedication and more than 200 parliamentarians have contributed soil to it from their constituencies.

Der bevolkerung mirrors a population’s inherent diversity, and the spontaneous chaotic growth symbolizes democratic process.

Hans says:

‘In an extremely controlled building, the ecosystem of imported seeds in the Parliament’s courtyard constitutes an enclave of unpredictable and free development. It is an unregulated place, exempt from the demands of planning everything.’

For me, its also a recognition that human effort cannot expect to successfully, and should not aim to, regulate our whole world’s complex ecosystems. We need to look for synthesising learning opportunities instead.

Art while working on many levels is not just reflective but sometimes highly dangerous. this often occurs while it is holding society accountable and there is no better example of this than John Kani the a multi-award winning South African playwright, actor and director. During the apartheid regime, he performed ‘protest’ works, acting alongside whites in a theatre troupe. The play he recently presented in Australia, Nothing But the Truth is a tribute to his brother, who was shot dead by police while reciting a poem at the 1985 New Brighton funeral of a nine-year-old girl who had died after being hit by a tear gas canister.

He says, and forgive me as I cannot manage his marvellous accent:

‘the artists are thermometer, that measurer change in our society. When governments become autocratic and begin to abuse the power entrusted on them by the people, they begin to get worried, about what artists are doing. They look at writers, they look at journalists, they look at the media, anything that is word they begin to censor and to concentrate on.

Some of the actions governments do is by reducing funding that’s a form of censorship, by cutting budgets for the arts and culture development, that’s a form of censorship, That’s when people must wake up and realise if they do this they’ll go to education the cuts will go to social services the cuts will go to health, and the cuts will only never touch the budget of the state and the budget of defence. So we must always be vigilant, as artists, and as a society and I believe the society depends on the artists, the writers to constantly remind them that they have a responsibility to nurture and guard jealously the democracy they are enjoying. They must never take it for granted we inherited from our forefathers who paid in blood and life for the freedom we enjoy today.

So artists, he says,

‘are a very important component of that guarding structure, that keeps governments on check, that gives communities all the time, never forgetting human decency.’

These guarding structures are vital – bearing witness can be highly dangerous.

This is Marelle Pereira holding a picture of her father, Fernando who was killed in the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior by French Government agents in Auckland harbour. She was eight years old at the time.

Sadly there are many other well known and not so well known examples.

Art as I said earlier provides a dot point.

That is a statement, a moment of clarity, an understandable encapsulation of complexity, and an emotional link.

This picture is by Angus Rayner couldn’t make it tonight. He’s a friend so I know that he will be comfortable with me mentioning some of what lies behind this picture. He was in the cafe at Port Arthur during the massacre.

You can see some of that chaos in the picture as well as other aspects of our world including obviously the environment.

His recent exhibition was launched by Nick Xenaphon.

Nick called this art:

‘gutsy, confrontational, and direct,’

and he also reminded us of what Picasso said:

‘art washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life’

art does this and more.

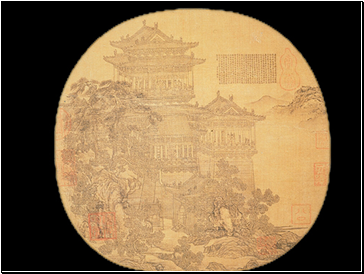

Thus drawing of the Yueh yang tower, a tsang dynasty (AD 618 – 901) structure shows small groups of people exchanging information with each other.

This drawing is by Hsia Yung famous for his depictions of architectural subjects.

During his time small groups of Chinese insurgents were banding together and being joined by Chinese deserters from the ruling Mongol army, slowly eroding the Mongol stronghold on their land.

RL Wing uses this drawing to symbolise the I ching trigram 59 – reuniting. There is a particular message for those involved in creative projects. That is the importance of this work in creating a commitment to a common cause and the development of the civilisation and well-being of the individual.

Artist Wing says have a social responsibility – to avoid elitism and egotism, to look for the symbols, rhythms and patterns that have long inspired mankind and to reunite people with their reality.

I hope I have given you some inspirational examples of this tonight.

Some upcoming events illustrating and seeking a synthesis

Next week Waking in fear and living in hope – what kind of art do we need now? the first of 3 forums in Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane kicks off.

Re-imagining a global future through dialogue and action TippingPointAustralia explores ways we can adapt to and mitigate functionally, culturally and socially the effects of climate change.

There are free public events covering hope to silver linings to citizenship.

Or, for an environmental self portrait of America, see Chris Jordan‘s great site (click the pictures to zoom)! Plus check the full list of TippingPoint speakers, participants and their websites.

good one Simon, Im sure you can contribute a lot to Tipping Point!