Climate change: A relationship problem

You are alive at the most important moment in history, the time where you can make the biggest difference …

We might say our souls consented to be here for this and that it’s an honor to be here at this time

How might our hearts break open and not breakdown? What does it look like when we widen the solution space, opening to potentials for radical beneficial transformations?

Introduction

Welcome to this wonderful talk with Terry Patton and Karen O’Brien. I like it a lot as Karen and Terry open up solutions—spaces and potentials for positively transforming our world.

This focuses on our climate emergency. Yet the solutions deliver numerous wins.

Karen and Terry start with what we already know—how fast climate change is hitting us. However, this is not a talk about the facts. It’s about widening the solution space including our own predispositions and beliefs. At the same time, collective trauma—our personal and interconnected emotional responses—are central to such shifts. Karen (and Terry) approach this with a genuinely integrated view opening up far more possibilities. Particularly the potential to reconsider and be challenged.

Importantly, this is a highly practical journey. It’s grounded in what is politically possible, what is happening in the here and now. In particular these are the signs of radical and swift shifts—what we miss when we think about the world based on how it currently is.

Watch and/or read the edited transcript below. It is part of the Collective Trauma Online Summit last year. Terry was one of four hosts. Karen is a professor in the Department of Sociology and Human Geography at the University of Oslo, Norway.

Karen is also a member of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and one of the co-recipients of its Nobel prize. She’s the co-founder of cChange—an initiative that supports transformation in a changing climate. She has over 30 years of experience in climate change research. She uses an integral approach to explore and promote deliberate transformation and to support sustainability. Her current research is emphasizing the role of creativity, collaboration, empowerment, narratives, adaptation and transformation processes—including the roles of worldviews and paradigms in generating conscious social change. She participated in four reports for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and, as part of that, she was the co-recipient to the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize.

In addition, she’s acknowledged by the American Association of Geographers for excellence just this year. Along with academic articles, she’s published, written and edited numerous books.

We have more options than we think

When people think about problems such as climate change sometimes this space feels overwhelming. It can be somewhat traumatic and encourage us to shut down.

However, we tend to base what is possible in the past. It’s like our ways of doing things never change. In reality that we’re constantly changing—this opens up many possibilities about what we can consciously create, removing many, self-imposed, limits

We’re here right now. There are ways of actually going deeper that will empower you to be able to be a bigger part of the solution. Empowering ourselves, especially going from that personal sphere into the political sphere, into the collective, into being able to connect with people, is important.

Interview: What we already know

Terry: I’m really excited that Karen is here and that we’re getting a chance to hear her because of the existential challenges that we face. I think this is absolutely relevant to our personal and our collective trauma right now. In some sense, all of our traumas are activated by our ecological predicament. There’s really nobody I know who is more deeply knowledgeable and able to be with all the different dimensions of this than you are. So, I’m really grateful you’ll be here with us for this next hour talking on Climate change: A relationship problem. I love that you chose that. Thank you. Thank you.

Karen: Thank you Terry and thanks for inviting me here to talk to you tonight.

Terry: Can you just lay out maybe things that we already know but that we tend to tighten up and exclude from our consciousness? The basic facts?

Karen: I think that just to bring it right home to where we are at in 2019, we actually know that we are responsible. Humans are responsible for changing the global climate. We have this based on observations, evidence, understanding of the climate system. We know that greenhouse gas emissions have been increasing dramatically since the industrial revolution. We know that the more greenhouse gases you add to the atmosphere the more heat is trapped. And we know that there are many different types of feedbacks in the earth system, feedback loops that are in some cases amplifying the warming and other cases dampening it.

A lot of the feedbacks that scientists are most concerned with are amplifying feedback loops such as more gas going into the atmosphere, trapping or holding more heat and melting ice. This then changes the reflectivity of the surface of the earth—less solar radiation is reflected to space.

There are many different loops: the melting of permafrost, changes in cloud cover. We have many cycles that are really accelerating the rate of change. It’s a complex problem and system. Humans are doing a dramatic experiment on the earth as a whole system. Where we’re at right now, in 2019, is that we know we’ve contributed to about one degree Celsius of warming since 1880. Our efforts really are focused on trying to minimize the warming now to two degrees, as agreed in the 2015 Paris agreement, and ideally 1.5 degrees Celsius warming.

In a nutshell we are changing the climate. We have to reduce or mitigate greenhouse gas emissions by reducing the use of fossil fuels, changing land use and many other things. But, we also have to adapt to some of the impacts that are already coming and transform our relationship to the earth.

Terry: One of the things that I especially appreciate is that you’ve been going to these IPCC meetings for so long and you’re steeped in a field that’s got lots of vigorous debate and different perspectives. There are people who think that the methyl hydrates or methane releases from peat bogs, tundra and the ocean floor are going to accelerate things so that we’re going to have near term social collapse. And then you have the climate skeptics on the other extreme.

The IPCC has really cut a kind of a middle path among all of these things. But, the actual data seems to be that changes are more rapid and intense than identified as our worst case trajectories just 10 or 15 years ago. How are you seeing things now?

Karen: I think that you’re absolutely right. When I started working with climate change in 1988, I kind of had this idea that eventually, by the 2020s, we would be able to see a statistical signal in the data. What wasn’t expected was the rapidity of actually seeing impacts on the ground and seeing changes in front of our eyes. Scientists, by nature, are skeptical. They’re trying to take in all different perspectives, trying to present a very balanced view, not go overboard. In this field called earth system science it has been really important to look at all the different connections.

But, we’re really seeing is a lot of drivers going along faster than predicted. Sometimes new things pop up—when I first started studying climate change ocean acidification was not an issue. Now it’s a serious issue. Discovering feedback after feedback we now have potential thresholds and tipping points, that’s the real concern. We don’t know how close to those tipping points we are, where it becomes dangerous, catastrophic climate change. That has a lot of scientists worried especially those who are studying methane releases, the melting of ice sheets or the drying out of the Amazon.

A few years ago was the first time we saw droughts in the Amazon. We now see dramatic wildfires caused by human activities. There’s a lot happening. It is very hard to take in the complexity.

One thing we do know is that humans are actually influencing global systems—wow, we can influence the whole world’s systems. Consequently, we can influence this deliberately in another way. That downplays the notion that we’re too small to make a big difference—an idea has been very prevalent, especially among skeptics. Now we’re becoming self-aware, aware that change is imminent.

We are going to transform one way or another. The last IPCC report I worked on was the fifth assessment report. In it, what we really say is the future is a choice.

Terry: I’d like to ask you to elaborate on what you think already baked in, or at least likely, societal human impacts. Even turning around political-collective will and doing a lot of the things we know are important, we’re still going to see a warming world. What is already going on is pretty disruptive, this weirding of weather, these superstorms and fires.

Karen: If we had a magic wand and could stop all greenhouse gas emissions today, warming will continue for several decades. A lot of the heat is taken up by oceans, like 90% of it. It’s like having a pot of hot water in your kitchen. It takes a while for it to cool down. The warming of the oceans and the greenhouse gases that are in the atmosphere have a long lifetime. There’s a momentum, an inertia, in the system—we’re going to be adapting to changes over the next decade. And, at our current one degree Celsius increase, we haven’t seen anything yet in terms of the real impacts.

This is a relatively small change but people are talking about changes of two, three degrees or four degrees Celsius in this century. When you look at all those feedbacks and the consequences, it’s very hard. We can try to make guesses but in many cases we are already seeing a lot of impacts now that are catastrophic for some communities, some species and people who are displaced from their homes. You can just amplify these types of things but we should also expect that there will be concatenated disasters—we’re moving into a non-analog future that we can’t prepare for.

It is not like the drought in the 1930s in the USA or, the little ice age or anything that has happened before. It’s really terra incognito for all of us. Yet we know enough to know that we actually need to be working on reversing change. It’s a massive challenge but science also shows that it’s possible too… we have the solutions we need.

Humans collaborate all the time—e.g. we build markets for exchange, living and socializing. Now we have to work together on a global scale.

The good news is it’s not just the idea humans that are creating the problems—humans are the solutions. Humans are the most powerful solution that exists to climate change. We are the ones that create the technologies. We are the ones that actually are responsible for the way we organize society.

Video

Part 1 of Karen and Terry’s interview is transcribed in this post.

Or watch the first parts of the interview below. Two segments, part 1a:

Part 1b:

One thing we do know is that humans are actually influencing global systems—wow, we can influence the whole world’s systems.

Consequently, we can influence this deliberately in another way. That downplays the notion that we’re too small to make a big difference—an idea has been very prevalent, especially among skeptics. Now we’re becoming self-aware, aware that change is imminent.

Widening the solution space

Terry: One of the really hopeful emergences that we’ve seen just in the last two or three years is the Drawdown project that you’ve been a scientific advisor on. It identifies proven changes in our behavior and systems that would enable us to not only to eliminate the current trend of adding carbon to the atmosphere but to begin to draw that amount of carbon down.

This conversation is around doing everything positive possible, we’ll get into a lot of different important points to make about that. But I know you’re also heartbroken to see all of the inevitable death, loss and degradation that seems to be baked in. I find myself wondering whether you do feel hopeful that we can hold the warming down to two degrees? For example, I’m thinking about the horrific rise of division, hostility and even ethnic violence that has already accompanied climate migrations. They are probably tiny compared to future ones.

Karen: It’s a great question because there’s a big difference. The last IPCC report on 1.5 degrees really showed the gap between 1.5 and two degrees Celsius warming. Even with that warming, at the very best case with the lowest scenarios, it’s 30 or 40 centimeters of sea-level rise. That has dramatic consequences for many coastal communities and coastal cities. Some cities will really have to be thinking about how do we move people? How do we withdraw?

The conversations are hardly there yet for big cities like Miami and Lagos. Yet there are many places that are already feeling water rising. They’re faced with should I stay or should I go right now? When we look at the impacts of climate change the vulnerability to those impacts is often very much social. It’s about how do we organize society? What are the options? Do we have early warning systems? Do we have security nets to help people move? When there are water shortages it doesn’t always lead to conflict, are there institutions available that can help to manage those types of conflicts.

When change happens you, you either shrink or you grow.

The fear is that climate change can be like an additional trauma to people, really devastating and cause them to just kind of draw very tight lines about us and the other—that we will not necessarily take in the big picture, we are one connected people.

Norway, for example, is not going to be a winner in climate change. Nobody is going to be a winner. There might an idea of relative winners and losers but, because we’re so connected biophysically and economically, culturally and socially, the challenge is to be able to handle the losses that are coming. We are losing species, we are losing communities, we are losing ice, we are losing.

There are a lot of things that won’t be the same again. Yet, we can do so much better—there is still that window of opportunity in the next dozen years or so to really bend those curves. You’ve mentioned the drawdown project. When Paul Hawkin first wrote to me and said here’s the most ambitious plan ever to reverse global warming, I was like, no you can’t, we can’t reverse global warming. He’s like, well our models are actually showing that. There are a hundred solutions. There are, if we keep carbon in the biosphere where it belongs, there’s a lot we can do even acknowledging lots of assumptions in those models. What I like about drawdown is it widens the solution space. It brings in all the different diversity of solutions such as those related to food.

Lots of solutions are related to connected pieces such as the education of girls or things that can really have multiple benefits in general for society. When we start to widen and deepen the solution space we see that it’s really everybody who has a really important role to play in this great transformation that’s happening.

Thinking from new paradigms

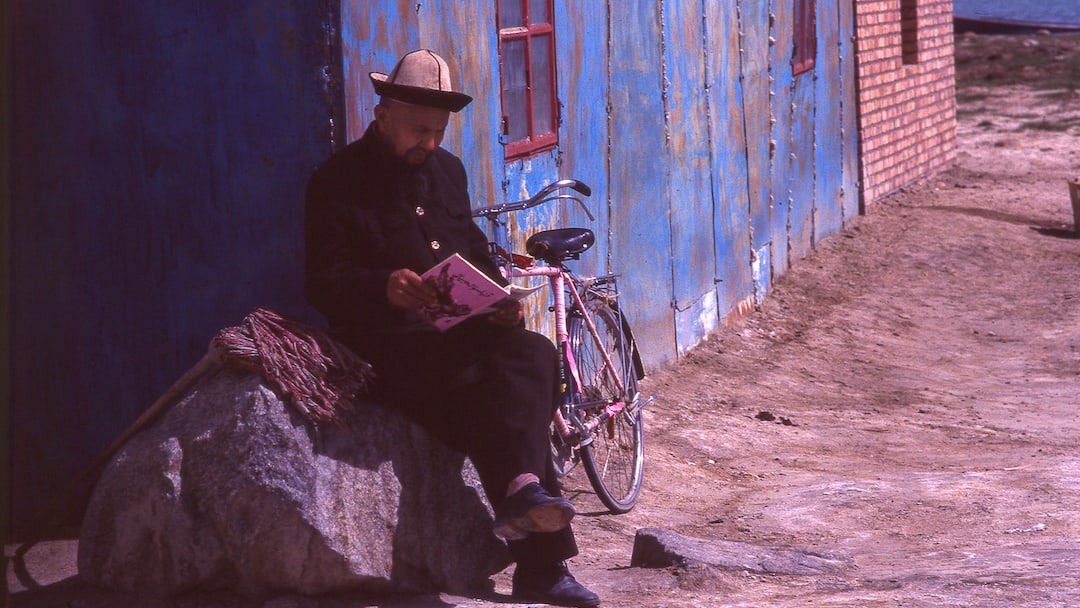

No room for a pool table indoors? Widen the solution space!

It’s about how do we organize society? What are the options? Do we have early warning systems? Do we have security nets to help people move?

Project Drawdown

In the short video above, Paul Hawken explains Project Drawdown—solutions that come together, deliver multiple benefits and are more than feasible to implement.

Take the solutions together, cumulatively, and we can actually reverse global warming.

What I like about Drawdown is it widens the solution space. It brings in all the different diversity of solutions such as those related to food.

Collective trauma

Terry: Which brings us to the reason we’re having this conversation in the midst of a summit on collective trauma. The human emotional toll and overwhelm are important.

I think we thought, oh, we will see the facts and respond. What we’ve discovered is very much like trauma, people have shut down. They’ve been wanting to go into denial, we’re conditioned to resist these ideas. Maybe we’re sometimes too traumatized to do what we need to do. How are you seeing and feeling about trauma in the midst of all of this?

Karen: I think many people don’t know how to hold onto climate change. It is overwhelming, we want to turn away. I often mentioned that I don’t get invited to many parties because I think it is like, ‘oh, she’s just going to raise climate change at the dinner table’.

One thing we’ve really learned within science and communication is that it doesn’t work to only talk to people’s heads, to fill us with facts. Data and evidence don’t really help. You have to tell stories, you have to connect with our hearts, you have to connect with values—the deepest values because we have different worldviews, different identities and beliefs. We touch each other in different ways.

Consequently, there’s a huge engagement within arts communities. They’ve defined other ways of not just communicating the science but of really dealing with, embodying, what’s happening to us collectively.

The trauma dimension, really healing that trauma, can release a lot of the energy, energy we need to be able to face, head-on, the challenges, now and in the future. This is especially for young people who are almost getting this problem dumped on them. We need to be able to show them that the possibility space is much bigger than they think. That is something we have to believe, and enable in ourselves, in order to communicate it to young people. We can’t try to get people to think something we don’t authentically understand to be true.

Terry: There must be moments when you see the trajectory of change, you feel overwhelmed, you feel a sense of despair and begin to think an apocalyptic vision may come into being. And then other times when you feel more heartened.

We all have stuff, personalities in dialogue, different voices and different points of view. And, I know there is another interpretive form which is that, after we face the darkness, after we recognize that we may be the last generation or two of people growing up imagining we could take the future for granted, we might discover incredible gifts. We might say our souls consented to be here for this and that it’s an honor to be here at this time.

There’s an opportunity to tell a story with the way we live our lives that express our values and that this is perhaps a sacred opportunity, that it is inspiring to us and, even in the worst of worst-case scenarios, it’s still possible to be a force of all of the best in the human spirit.

Karen: That’s beautifully said because I think it’s part of what drives me,

I read the news a lot. Reading the latest news on Antarctic ice or species loss or … It just does break my heart. I can remember editing the IPCC summary for policymakers where you look at what the probabilities of sea-level rise and you know it is heartbreaking. It is so hard to actually imagine and we just take it kind of dryly. But we’re talking about not just like the beach moving up. We’re talking about water covering vegetation that shouldn’t be underwater, toxic waste, all these types of things.

We can’t even fathom what we’re actually doing, that border between oh my gosh, you know, it’s game over. To, no, we can actually do much better.

I remember when I was a student taking a course on the extinction of species. The professor said you are alive at the most important moment in history, the time where you can make the biggest difference. It really was one of those moments where I realized this matters. The work we do really makes a huge difference right now. I think that, hold that, to be able to deal with the loss, the grief and to look in front at what could be coming.

Then again there is so much potential and possibility on this planet right now for social change. That’s where I’m very interested, social change and transformation is the sustainability. In many ways, like a lot of my earlier research on impacts, vulnerability, adaptation and human security—looking at what the problem was—it has really twisted towards what the drawdown project is. Let’s look at the solutions and how we do it in an ethical, equitable and sustainable way? That really drives my research now, getting into that deeper part.

It’s how do you connect with people who don’t see the world the same way that you do? People who are traumatized, people who have been oppressed, people who have given up on caring for or just don’t think that life is worth it, don’t care what happens.

In my own development, I’m thinking of a paper probably around 15 years ago on winners and losers. Where did this idea of winners and losers come from? Is this a natural inevitable evolutionary idea, kind of like Darwinian, or is it socially and politically constructed and generated?

My aha moment was that not everybody cares about the losers. That was a real wake up call for me, that there are people who would say like, “I don’t care if the whole Greenland ice sheet melts because it will reveal some interesting geology, mineral wealth or something.”

It breaks my heart, even more, to think that there are people who couldn’t care if millions of people lose their homes because there’s gold. We’ve all read those fairy tales and fables, the King Midas sort. I think, for many people, social justice (and not just for humans but for nonhuman life) is a powerful, strong driving force. That hope is that our hearts do break open and not break down, right now.

We all have moments where we’re overwhelmed by emotion, not always negatively… This interview explores our emotional climate change responses, releasing energy and collective trauma.

There’s an opportunity to tell a story with the way we live our lives that express our values and that this is perhaps a sacred opportunity, that it is inspiring to us and, even in the worst of worst-case scenarios, it’s still possible to be a force of all of the best in the human spirit.

Healing collective trauma

In this short video below, Thomas Hubël talks about responsibility—the ability to respond. How do we respond to the news, the massive amount of information we are exposed to every day.

We cognitively know that the Holocaust was terrible and we cognitively know that dictatorships and Wars and massive natural catastrophes are terrible but actually we don’t feel it we feel only in symptoms. We feel the after-effects of trauma, domestic violence attachment trauma and so on but actually the route is much deeper …

Terry Patten and Thomas are two of the four co-hosts of the Collective Trauma Summit. Terry interviews Karen.

A genuinely integrated view

Terry: The way you’re talking about it now reveals why I thank you so much for your career’s worth of work. It has both the scientific rigor necessary to participate in that domain and a genuinely integral view.

Karen: You are looking at the interior changes that individuals and groups are challenged to go through. The challenges in collaborating. The challenges of agreeing and adapting. The kinds of conflicts that get created. And then challenges the of conversing across those boundaries, the transformation of the worldviews and paradigms out of which we’re understanding all of this. These define and determine what we can do.

Terry: So often the science around climate change is looking at it as if it were merely a technical problem rather than a full spectrum, four-quadrant, affair (an integral theory approach).

The fact you’re looking at this in an integrated way—and you’re a respected voice in the most important forums where this conversation is going on—is heartening to me. This opens a transition in our conversation where we can talk about what those challenges are and where you see opportunities in terms of adaptive leadership and collaboration.

Karen: I think that the distinction between technical problems and adaptive problems is really important. It’s like we have all these goals. We kind of have targets. We’re really just trying to, you know, have more solar panels and more people on bicycles.

We focus so much on technical behavioral dimensions but the adaptive challenges are really about mindsets. They’re about the way we see the system, the way that we relate to the system—what are some of our assumptions and beliefs about that very system. If we treat it like that we’re bound to fail. It’s not that we can’t figure out how to store solar energy in batteries. It’s that we’re not looking at that full spectrum of the alternatives that are available right here and right now.

When I look at adaptive challenges I really see them as very personal too. They’re about the way we individually and collectively see the world and the assumptions we have. They’re very political because they’re really about what we take as the given—what we just accept as ‘this is the way life is’, this is the way society has been formed, this is the way people are. I think combining those: the practical; the political; and, the personal together really is an integral perspective. It’s taking the subjective and objective, the interior and exterior, and bringing them really together in a way that gets people to relate to the problem in a deeper way.

It’s funny because when I talk about this, about the importance of beliefs and values and worldviews and paradigms, a lot of scientists will just bob their heads and go, “yes, you’re absolutely right, we need to change people’s beliefs and values and worldviews”.

From a developmental perspective, you realize, wow, nobody likes to be changed by somebody else. Often that’s very oppressive. It’s manipulative. It just backfires in so many ways. It is trying to get people to realize, when we talk about that personal part of the adaptive challenge, that this is about challenging your own assumptions, your own beliefs, dealing with your own trauma. It is dealing with everything so that you can show up in that political sphere, so that you can relate to people who are scared, who don’t really see the same world as you do or have different concerns.

At its core it’s to make connections. That’s really like my research now—it’s called adaptation connects—adaptation as transformation. How do we empower people to see the transformations that are right in front of us?

I think that type of work really resonates with many people today. In the climate community, the discourse has changed a lot in the last five years. Values, emotions, wellbeing, empathy—words that were not there 10 or 20 years ago—are really coming up. We’re starting to see a real yearning for a more integral approach to problems and the solutions.

Collaborating

The challenges of collaborating. We have managed to find answers, to work together, throughout history. Karen and Terry talk about how an integrated view can help us now with global problems.

Integral?

There is a lot written on Integral. However, for applied shifts see the Integral tag > Articles about how it helps created significant benefits, helps us see past our blind spots and more…

I think that type of work really resonates with many people today. In the climate community, the discourse has changed a lot in the last five years. Values, emotions, wellbeing, empathy—words that were not there 10 or 20 years ago—are really coming up. We’re starting to see a real yearning for a more integral approach to problems and the solutions.

Reconsider and be challenged

Terry: To challenge ourselves, what specifically might you want to ask people to reconsider? To be challenged by?

Karen: I often ask about beliefs because a lot of the scientific community says yes, we can limit warming to two degrees. Then I’ll ask how many of you really believe that we can do that? You get very few hands in the room. I’ll ask, how many of you are very flexible with your beliefs and your belief systems? People say… not really.

What would we need to believe? What comes up when we say we can limit warming two degrees Celsius? There are a lot of beliefs. People hold: oh, it’s already too late… We blew it 30, 40 years ago. Others might say: people never change… people are done with development by the time they’re 25. Or: the models are saying that we cannot limit warming to two degrees.

I look at models and I ask what are the assumptions? Are models always right?

An example is some of the integrated assessment models that say there’s a 5% chance that we can limit warming to one to two degrees Celsius by the end of this century. But, if you look at the actual scientific paper, at the very end they talk about their assumptions. These include no new climate policies and that renewable energy will not be competitive with fossil fuels.

It doesn’t focus on collective cultural change, shifts in consciousness, widening circles of care, changes in what we eat… Non-linear social change is often not included in models.

Getting people to reflect on what are the beliefs that you hold and what is your sphere of evidence is important. One thing I often give my students in an exam question is to place them in the year 2100. I have them look back and say, what were they thinking, you know, back in 2019 and, you know, where was, you know, what were they, how was, what was their view of the world?

Also what was missing? What were their blind spots? What could they not see that was like right in front of them? That was there as the possibility and potentiality at that moment. Getting people to really start to reflect, oh, do I also have blind spots? What that might they be?

I think that’s a really good exercise for all of us. When we start to think about the future we tend to colonize it with our views of the world right now (as if this is the way it always is).

Yet, we know that future generations will see it very differently. They will be very happy about anyone who actually saw the possibilities that existed right now. Someone who said, the thousands and thousands of people who actually said, we can do something about this. We can do better.

Terry: In this collective trauma summit we’re talking with a community of people who are interested in transparent communication. They are generally interested in the transformation of their own consciousness and mobilizing compassion, self-compassion, in relation to our trauma.

People with these beliefs have tended to be viewed as a kind of a new age fringe—the mainstream has even excluded us to some degree. We sense that although what we’re doing is good there needs to be this transformative shift. We need to go through, maybe, multiple profound shifts, even in our way of being—the whole picture isn’t going to change without us changing too. I need to challenge myself, challenge my assumptions. What can you tell me that might help me show up better?

Karen: I can really relate to that. Ridicule is a powerful way of dismissing someone.

There are so many people who are really feeling it and hurting. I think we all have to really occupy a new paradigm and show what it is to actually live to these ideals. You’re there and many people are ready to come there. I think it’s almost, you know, a giant consensus that the world we have created right now is not working for many, many people.

To be able to be teachers, healers, to be the ones that can, through very gentle actions, help people to move when they’re ready is like being an attractor. A lot of people are opening up. If you’ve ever had a crisis where your worldview no longer works, you know about such shifts.

We’re here right now. There are ways of actually going deeper that will empower you to be able to be a bigger part of the solution. Empowering ourselves, especially going from that personal sphere into the political sphere, into the collective, into being able to connect with people, is important.

The good news is it’s not just the idea humans that are creating the problems—humans are the solutions. Humans are the most powerful solution that exists to climate change. We are the ones that create the technologies. We are the ones that actually are responsible for the way we organize society.

It starts to bring people into looking more closely at these issues. Issues of power interests, the things that have led to exactly the world that we have right now.

We have a collective voice. How do we work better together?

This gets into the idea of the individual is the collective individual trauma. You heal yourself and you heal a wider field too because you are more of yourself can show up.

My short answer is the time is ripe right now for many of these views to just come into the dialogue about climate change. We know so much about what’s going on. We’ve known that for decades.

The real challenge is to focus on how do we transform in ways that are not just engineering or things that are from that same paradigm. How do we transform when climate change solutions, actually, address many other problems, social challenges, that we have right now in the world.

End of part 1

Karen and Terry continue to explore the solutions in part 2 (coming soon).

What do we expect to see? What do we usually think, how might we reconsider our sense-making?

Here’s to being challenged, we’ll know we’re living more fully!

It’s not just the idea humans that are creating the problems—humans are the solutions. Humans are the most powerful solution that exists to climate change. We are the ones that create the technologies. We are the ones that actually are responsible for the way we organize society.

It starts to bring people into looking more closely at these issues. Issues of power interests, the things that have led to exactly the world that we have right now.

We have a collective voice. How do we work better together?

This gets into the idea of the individual is the collective individual trauma. You heal yourself and you heal a wider field too because you are more of yourself can show up.

Resources

Links and posts

This interview is part of the Collective Trauma Online Summit. See its site for background and further interviews here >

Terry Patten’s work is featured on A New Republic of the Heart here >

Karen O’Brien’s cChange, Transformation in a Changing Climate is here >

Integral theory gets applied across organizations, development, climate change and much more. It shifts people’s perspectives helping us to see a bigger picture and answer traditionally stuck problems.

For example, see South Australia Health’s outstanding integral performance story here> and Addressing polarisation, Assisting our better angles to come forth, here > and basic background on Integral here >

For more stories see the Integral tag here >

Images are from Kashgar and Karakul, Xinjiang, China and the Karakoram highway, Pakistan. Credit Festina Lentívaldi, (be) Benevolution Reuse: Creative Commons BY-NC 3.0 US (except video screenshots).

It’s not easy breaking habits!

1 Comment

Subscribe

Get the newsletter (story summary).

Recent posts

Coming home

We belong to and are of the Earth but we bypass our sense of belonging. I missed this leaving home and my story mirrors our larger, human-wide journey. What do I need to come home?

Soulprint: Peak nature

Extraordinary: a paradigm shift by 147 governments and the UN endorsing “humans and nature are spiritually connected.” Invitation: to build on this for yourself and all of us.

We are in a portal

I’ve a deep knowing: we humans have shifted. That’s disorienting so here’s 3 handrails to help: this is sourced in bliss; lubricated by peak oil; agreed by UN & 147 nations; and, all with dragonflies!

Loved the videos, and Karen and Terry’s perspectives on the opportunity afoot … to “go deeper in ways that will empower you to be a bigger part of the solution”, to grow and evolve and bloom into more wholeness, for ourselves and our communities and all life. hmm. Grow up and bloom. Yes! Would seem like such an obvious attractor, if only we could see it en masse. Gotta be more fun than moving into some underground psychological bunker provisioned with a life-time supply of fear.

I like Karen’s comment too that “one way or the other”, we will change to adopt sustainable living practices. It is inevitable, so might as well get started now and be part of the solution.

I am left wondering if that becomes the defining traits of those who survive and thrive in periods of such disruptive change … the arts of sustainable, adaptive living. Kind of like building a healthy immune system for my humanity, to protect me from the pathogens of hubris and fear and the impulse to contract and defend when the heat is on.

On the upside, there’s the invitation to get closer to nature, to remember all the compelling reasons why gratitude and awe are the only sane responses to what is actually going on in every moment, in every breath, in every small miracle of existence.

Seems the price to be paid is the willingness to sacrifice convenience and be happy to spend more time on the recurring tasks of life; gathering and preparing natural food, cleaning without chemicals, washing and reusing packaging, repairing clothes, fixing broken things and being a little more willing to go a little slower in everything and use less fuel across the board. Not as hard as it sounds, and quite fun and grounding once you get the hang of it.

And learn to love insects again, and not be afraid when a natural thing with a sting comes within range. I am endlessly amazed at how frightened are our retreat guests to get close to bees for fear they will turn into demons intent on hunting them down. Never seen a bee do such a thing, or a wasp or even a snake. A little caution is well advised here in sub-tropical Queensland where half the things that bite can make you seriously crook, but to my eye, the beauty outweighs the threat by orders of magnitude.

Back to the vids… Sending blessings to remember to look up and drink the light from time to time, and thanks for all the work Terry does gazing down into the scary depths of how dark we can become.

Time for rest mon self. Nice to get some of this stuff into words. Thanks for offering such an enticing invitation.

Sweet dreams,

Terry